THANKS TO LOCKDOWN, IT’S BEEN ALMOST A YEAR SINCE I LEFT MY HOMETOWN, so I was looking for an excuse for a day trip, to find something Toronto doesn’t have. As I’ve discovered for myself, the city has plenty of green space and waterways, but thanks to geography’s pitiless rules it lacks dramatic features, like deep valleys and waterfalls. When we wanted a lookout to survey the landscape around us, we had to build it: Behold the CN Tower.

Which is how I found myself in Hamilton, the city next door, which had the foresight to locate itself astride the Niagara Escarpment instead of a wide, sandy flood plain. The Escarpment, for anyone unfamiliar with high school Canadian geography classes, is the remnant of an ancient tropical sea formed nearly half a billion years ago. It runs from upstate New York near Rochester through southern Ontario to Illinois, and it makes Niagara Falls possible, along with skiing and wine grapes in Ontario and Wisconsin.

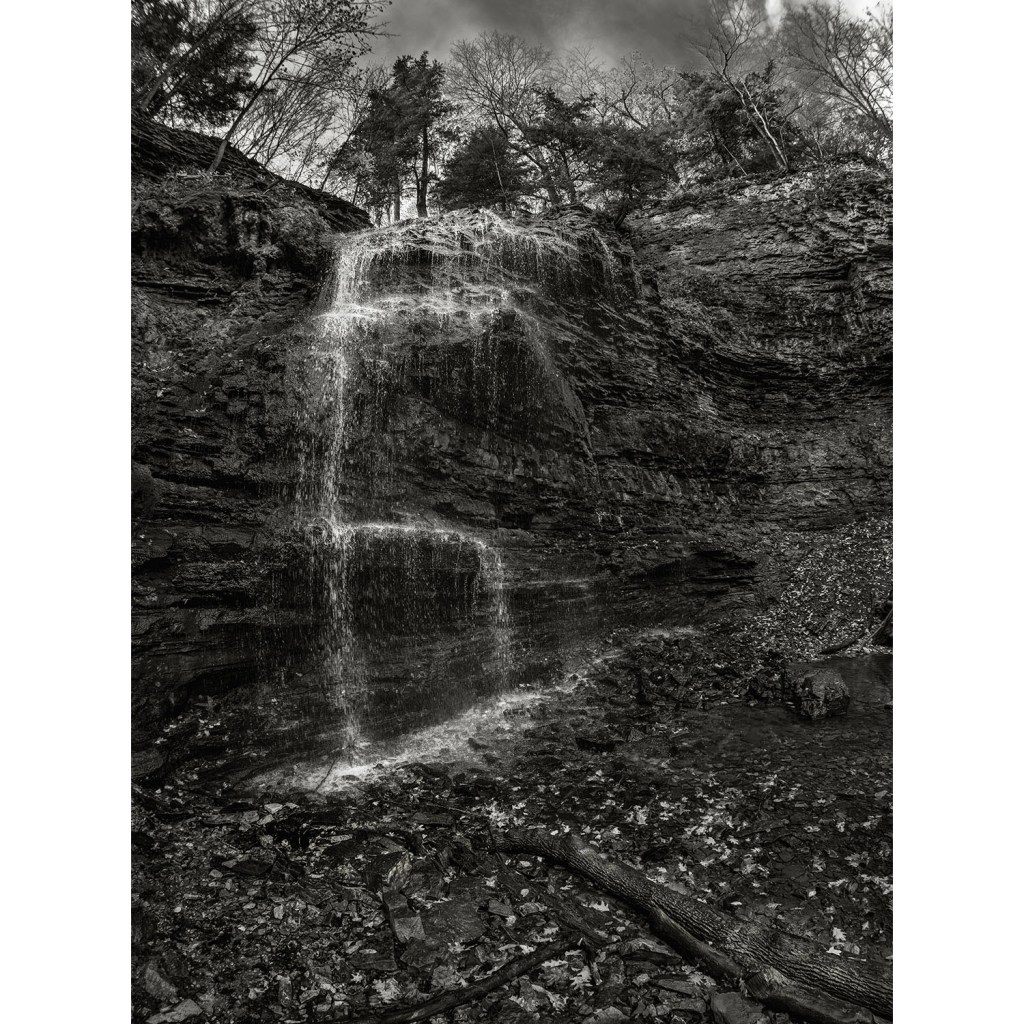

Ancaster, a suburb of Hamilton, sits on top of the Escarpment, and with my dad as guide and chauffeur for the day, we began with Tiffany Falls, one of the select handful of a hundred waterfalls in the Hamilton area that’s considered a “must-see” – just a walk in from parking, flowing year-round, and a proven hit with photographers. Fall has been dry so it’s hardly a raging torrent, but it still cascades down the face of the Escarpment, twenty-one metres from top to bottom.

It’s easily the most picturesque of Ancaster’s falls, a ribbon of water making its way from one rocky shelf to another, turning at right angles as it descends to the bottom of the cliff face. Tiffany Creek is just one of the streams and springs that feed Hamilton’s collection of waterfalls, named after a beloved local doctor who came to the area from Philadelphia at the end of the 18th century.

The walk to and from the falls follows trails at the bottom of the little valley that Tiffany Creek cut into the hard dolostone and the softer layers of shale and limestone running alongside it, most of this geology visible as a layer cake on the face of the escarpment by the falls. It’s hard to imagine now, but the falls was once a raging torrent when it created the valley, back when the glaciers were retreating. More recent history can be found in the crumbled remains of a kiln made of brick and local stones, on a little rise overlooking the parking lot.

The next stop is Sherman Falls, at the end of another steep little valley, carved out by Ancaster Creek. The name of the falls has changed many times, depending mostly on who owned the big adjacent private estate. It’s been Fairy Falls, Angel Falls, Smith’s Falls, Whitton Falls and Farah Falls, but the name that’s stuck comes from one of the founders of Dofasco, a steel mill crucial in Hamilton’s history.

Sherman Falls is one of the more substantial Hamilton waterfalls, a curtain of water cascading in two or three major steps down seventeen metres of Escarpment. On a weekday morning there are only about a dozen or so people by the falls, considerably less than you’ll find on a weekend, and nowhere near the crowds that might be here in the spring. With the water low, it’s possible to get much closer than I expected to both Tiffany and Sherman Falls with my camera and tripod.

Our next stop is a comparatively “tame” waterfall, and not surprisingly the easiest to access. Mill Falls is, as its name suggests, the onetime watercourse for a flour mill, the fourth on this site, built in 1863. With all of this waterpower available, you’d expect mills to have filled the landscape above and below the Escarpment in the area’s pioneer days. The building is now Ancaster Mill, a restaurant and event space owned and managed by the same company that renovated the deluxe hotel and spa complex in Elora, and with the same attention to detail and quality.

The watercourse at Ancaster Mill is a tributary of Ancaster Creek. At the top, it runs past the wedding chapel and through a contained and purposefully dramatic cascade by the restaurant patios. It continues down more naturally by the onetime site of the mill’s waterwheel, over rocks and rapids before it passes by a gazebo and the restaurant parking lot.

The trail to our last waterfall begins just by Mill Falls, with a hike that takes in the majesty of the Escarpment and its woodlands. A combination of the Heritage and Bruce Trails winds along the top of the cliffs on its way to Canterbury Falls. The Bruce Trail leads you through the woods to the falls, past long outcrops of Escarpment dolomite, zigzagging walls of stone with fissures that make it look like the long-abandoned ramparts of an ancient citadel

The falls finally appear ahead on the trail, seeming to sprout from the rock underneath a wooden bridge. A tributary of Sulphur Creek feeds Canterbury Falls, a long ribbon of water that falls in gentle steps nine metres to the botton of a curving valley floor. In the summer’s dry season the falls can slow to a trickle, but there’s been just enough rain this fall that the water flows clear and bright against the dark rock, surrounded by a carpet of leaves in orange, red and yellow.

Once you’ve found the falls, it’s worth your time to enjoy the trail that took you there. The Bruce continues along to the edge of the Escarpment as it looks across the Dundas Valley, where you’ll find another set of falls, including Tew and Webster Falls, but that’s a trip for another day. The rocks here jut out into the air above the trees, occasionally producing nice overlooks down through the trees to the valley.

On a day in the waning half of fall, most of the trees here have lost their leaves, and soar up into the sky, the roof of green gone for the season. It gives the forest along the path a cathedral-like feeling, and it’s easy to understand why the Escarpment has been designated a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, one of a dozen in the country. Thanks to the cliffs, the forest ecosytem along much of the escarpment is the oldest in this part of North America, boasting amont other things the oldest tree in Ontario, a dwarf white cedar nearly fifteen centuries old.

The Escarpment looks solid, but the soft rock beneath the dolomite cap is eroding constantly, and occasionally the weight of the stone at the top will heave out from the cliff and down into the valley. Fissures open up in the stone, created by expanding winter ice, forming hallways down between rock walls into the valley below.

The landscape can seem ancient, but it’s really changing all the time, albeit at a stately pace we can’t see. Between the bracing sensation of falling water and the rich, sharp aroma of fallen leaves, a walk along the waterfalls is recharging, a last gift before winter descends.

Photos and story © 2020 Rick McGinnis All Rights Reserved

Gorgeous shots, Rick. I used to ride my bike with a pack of kids every May 24th weekend when I was a kid, but have never seen the other waterfalls in Hamilton.

LikeLike

Oops! Senior moment. I used to ride my bike to Albion Falls….

LikeLike

[…] at the end of over ninety minutes travel by public transit. It takes less time to travel to another city, and in many ways that’s what the east end has always seemed to […]

LikeLike

[…] Butte, we pulled off the highway by Brooks Lake Creek Falls because, well, doesn’t everyone love a waterfall? Approaching the Absaroka Range near the end of the day’s drive, we pull off to get one of […]

LikeLike