FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION TOOK ME BACK TO IRELAND. A year after the blockbuster revival of the Star Wars franchise with The Force Awakens, one of the locations for the film had created a tourism boom around a pair of tiny, rocky islands off the southwest coast of Ireland. I had just begun working at the travel section of the national daily when my editor asked me if I wanted to join a trip to visit the place where, during the film’s finale, the budding Jedi Rey discovers Luke Skywalker in exile. This would be my first assignment, and it felt like an epic adventure.

The trip would begin in Dublin, where I’d meet up with our group – a collection of journalists from Europe, Australia and South Africa. We’d be hosted by Irish tourism, who were keen to showcase a whole new destination and the attractions that had quickly sprung up, to service travelers who wanted to see an ancient landmark that had somehow become part of the atlas of alien landscapes in the Star Wars universe.

We had nearly a whole day in Dublin, most of it at leisure. It felt momentous at the time – I was the only member of my immediate family to set foot in the country since the Great Famine had made us emigrate, first to England and Scotland and then to Canada. But my first stop was an errand for my wife – Glasnevin Cemetery, one of the world’s most striking graveyards, where members of her family were buried. I tried to spend as much of the day on foot, grabbing snapshots of the town, despite the pain from a new pair of hiking shoes that, unwisely, I had neglected to break in before the flight. My memories of the city are a chaotic rush, but the standout is that Dublin has an awful lot of pubs.

Our next day begins early, with a long bus ride across Eire to County Kerry and Portmagee, the fishing village that had become the focus of tourism to the Skellig Islands. Skellig Michael – a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1996 – had been chosen to represent Ahch-To, the watery planet in the Unknown Regions where the Jedi Order had begun, though the environmental and archaeological sensitivity of the site, not to mention the difficulty getting out there, meant that when further sequels revisited Ahch-To, filming mostly took place on sets constructed in nearby Dingle.

The Skelligs are stunning, a pair of sandstone and slate crags dramatically jutting up from the North Atlantic. It was difficult to get onto Skellig Michael even before Star Wars tourism began, and Little Skellig, its twin, is completely inaccessible – a guano-covered bird sanctuary swarming with wildlife. Despite the increase in boat tours from May to October, visitor numbers are strictly limited, even on days when the sea is calm enough to dock at the island. The Skellig Experience Visitor Centre on Valentia Island, across from Portmagee, has been opened for tourists who aren’t able to make a successful trip, and just in case weather prevented our own scheduled visit the next day from happening, Irish tourism booked us helicopter flights from just outside the visitor centre, flying over the water to give us bird’s eye views of the Skelligs.

The weather favoured us the next day – clear, cloudless skies that would accompany our group for the rest of the trip. We docked at Skellig Michael and made our way up the winding paths – a paved trail at first, and then a long series of steep stairs built out of the island’s slate, most them lacking handrails. If you don’t think you’re fit enough, or suffer from fear of heights, you probably won’t make it all the way to the ancient monastery ruins at the top. While gulls swoop overhead – bold enough to snatch sandwiches from lunching tourists – your trip up the steps is monitored by comic little puffins, so abundant that the Star Wars films had to digitally transform them into Porgs as an alternative to painstakingly erasing them from shots. What I heard, however, was the groaning purr of the nocturnal storm petrels that nest in the rocks, abundant but invisible.

The most natural rest stop on the way up Skellig Michael is Christ’s Saddle – the valley between the island’s two peaks. Which is fortunate for Star Wars pilgrims as that’s the spot where Daisy Ridley’s Rey finally encounters the hooded Luke Skywalker, handing him his old light sabre and fixing the aged Jedi with a pleading look as the camera swirled around them during the final shot of The Force Awakens. Of course, when we rejoin them a moment later at the start of The Last Jedi, Luke contemptuously throws his old weapon over his shoulder and stalks away.

At the top of the path is an early Christian monastery, founded sometime between the 6th and 8th centuries by Augustinian monks at what was, at that point, the edge of the world. There’s a graveyard, an oratory and a church, but the most distinctive buildings are the beehive huts, the cells where the monks lived. Built of dry stone without mortar, most are remarkably well-preserved considering their age, and the winds and weather they’ve experienced over the centuries. Life for the monks here, no more than a dozen or so at any time, must have been stark and austere, even when they weren’t enduring winter storms or Viking raids.

The monastery was abandoned and the monks moved to Ballinskelligs on the mainland around the 12th or 13th centuries. Skellig Michael was a pilgrimage site by the 17th century; two hundred years later the British government bought it and built a lighthouse on the island, and the first archaeological digs were done, revealing a human presence on Skellig Michael back to the Neolithic period. While Star Wars might have raised the island’s profile as a destination, and 2020 temporarily stopped the flow of visitors, it’s unlikely that the Skelligs will return to obscurity, so anyone planning to visit for either history or fantasy need to know that the seas might not be as calm for them as on the day I was there.

My advice for visitors, whether they’re a Star Wars fan or not, is to come here if you can. The Skelligs are one of those Wonders of the World, on a par with Machu Picchu, Stonehenge or the Pyramids; no matter how inconvenient or crowded getting there might be, the experience on the spot makes it entirely worthwhile. And while the subsequent Star Wars sequels might have squandered the thrill of The Force Awakens, the franchise is reviving itself with new stories like The Mandalorian, so it’s not impossible that it might find itself returning to the windswept cliffs of Ahch-To one day.

We made our way back to Dublin along Kerry’s bit of the Wild Atlantic Way – Ireland’s tourist route along the Atlantic coast. That took us across Valentia Island – a spot packed with destinations, though we had to hit them at a run. We went to the top of Geokaun Mountain – hardly a dizzying summit by the standard of, say, the Rockies, but it does give a clear view across much of the Kerry coast, and out to the Skelligs.

Hugging the shore, we visited Cromwell Point Lighthouse – built in the 19th century on the footprints of a 16th century fort – and the Tetrapod Trackway, the fossilized footprints left by an ancient and extinct creature across some prehistoric Devonian beach. There was a stop at the slate quarry and grotto chapel at Dohilla, and a wander around Knightstown, a pretty little fishing village on the way back to the mainland. Somewhere along the way we had Guinness ice cream within sight of the cows that provided the milk.

Press trips are a whirlwind at the best of times, a chaotic overload at the worst. This one was paced just enough that I was able to wander around with my cameras at every stop. Don’t ask me for any specific recommendations except that you should take the time to drink it all in if you visit Kerry.

I do remember that the food was excellent – surprisingly so, especially the seafood – and that even then the highlight of every meal was the freshly-baked soda bread with local Kerry butter. You could live on that stuff. Also, despite what everyone tells you about Ireland and rain, pack sunscreen along with the rain gear – a sunburn was among my souvenirs from this trip.

After a night in Killarney we were booked for rides into Killarney National Park on “jaunting cars” – traditional carriages that have exclusive use of roads prohibited to cars. We were on our way to Ross Castle, a 15th century tower house and keep that was destroyed by Oliver Cromwell’s Roundheads during the conflicts surrounding the English Civil War. We arrived just in time for a performance by a piper just outside the gates, which provided the sort of photo that you hope for when you obey one of the first rules of travel photography: Never say no to a castle.

From Ross Castle we drove around Lough Leane to Muckross House, the 19th century tudor-style mansion whose original owner was forced to sell after he was bankrupted by the expense of hosting Queen Victoria. Famous for its lovely gardens, it was given by its last owners to the Irish Free State, and its grounds became the nucleus around which Killarney National Park was built. This final full day in Ireland produced an avalanche of photos, only a few of which I have the space to share here. I had gone to Ireland to visit a place in a galaxy far, far away, though the trip was really more of a homecoming.

ON A COAST NOT SO FAR AWAY, AT THE OTHER END OF IRELAND, ANOTHER FANTASY WORLD WAS BEING BUILT. A year after my Star Wars trip to Kerry, I was sent to Northern Ireland, where HBO’s Game of Thrones had set up its production headquarters in buildings next to where the world’s most famous ocean liner had been launched a hundred years before. The series, set in a bloody medieval world of magic and dragons, had become an international sensation, and with season seven scheduled to air in just three months, a whole bunch of filming locations near Belfast had become tourist destinations.

The studios where GoT was filming many of its scenes is part of the Titanic Quarter, a massive urban redevelopment project centred around the old Harland & Wolff shipyards, where the White Star liner Titanic and its sister ships, the Olympic and the Britannic, had been built before World War One. The twin slipways where the Titanic and the Olympic launched are preserved as a massive open air memorial, within sight of the film studios, which was created around the shipyard’s onetime paint hall.

A museum, Titanic Belfast, was opened in 2012, and an old dry dock nearby contains the restored SS Nomadic, the only remaining White Star ship still afloat – a tender that had ferried passengers to the Titanic and other White Star liners while they were anchored in Cherbourg. It’s a spectacular, cutting edge museum that tries to tell the story of the Titanic in the context of the city and the country where it was built. Belfast and Northern Ireland have a lot of history, much of it in the last century violent and tragic, and while I was in town I felt obliged to explore as much of that as possible.

Belfast does not shy away from talking about the Troubles, the on-again/off-again civil war that overwhelmed Northern Ireland from the moment the Irish Free State split from British rule. In a downtown branch of Waterstones, the bookstore chain, a table of books was piled high under a sign that read “A History of Violence: Delve a little deeper into our troubled past.” There are “Troubles Taxi” tours that will take you around former hot spots with a helpful driver. I wanted to see what was happening with that troubled past today, so on a day off in the city I got on a bus and headed for the Falls and Shankill Roads.

The Falls Road runs through the centre of Catholic working-class Belfast; the Shankill runs through its Protestant neighbour. They’re right next to each other, which would explain the constantly simmering tension that characterized daily life in Belfast for decades. The area is much more peaceful today, but that violence echoes in the murals you see on walls in both neighbourhoods, many of them memorials to the martyrs of each side. Today they’re separated by the Peace Wall, a street of murals – some recalling the conflict, some hopeful for the peaceful future – running along Cupar Way, at a spot where barriers once divided the city’s warring population.

Nobody in Belfast wants to return to those times, when terrorist bombings were weekly if not daily, and the downtown was gutted and empty. Street life has returned to the city, along with tourism – I stayed in a boutique hotel downtown with a Steve McQueen theme – and Belfast even has its own version of Temple Bar, Dublin’s pub-and-party district. The Cathedral Quarter is a lot nicer than Temple Bar in my humble opinion, full of great restaurants and pubs that, at least on the spring night I visited, weren’t jammed with stag and hen parties. If your idea of Belfast and Northern Ireland hasn’t been updated in at least twenty years, you’ll be pleasantly surprised by the city today.

The next day began in the rain, with a drive north from Belfast along the coast through County Antrim. Our first stop is the little stone harbour at Carnlough, and the stone steps emerging from the water where Arya Stark crawled out of the canal in Braavos after being stabbed by the Waif in season six. We went on to the Cushendun Caves, formed by the sea and tides, and the season two episode where Davos Seaworth watches in horror as Melisandre the red witch gives birth to a shadowy creature that floats up through the rock to assassinate Renly Baratheon in his tent. The rain had stopped by the time we reached Larrybane Quarry, another season two location, where Renly holds the tournament where viewers are introduced to the amazonian Brienne of Tarth for the first time.

Our next stop is the fishing village of Ballintoy, which stood in for Lordsport, the scene of poor, luckless Theon Greyjoy’s decidedly underwhelming homecoming to his family and the watery isles of Pyke. The beach near the harbour is full of striking rock formations that set the scene perfectly for the raw, pitiless homeland of the Iron Islanders. It’s a great place to stop for an hour or two and take in the scenery, with its ancient little church and stone walls surrounding the harbour.

Northern Ireland was a gift for the people making Game of Thrones, with its centuries-old little towns hugging a coast peppered with sometimes brutal and awesome geology. It has a primeval aspect, only barely veneered by civilization – the towns and village that seem to hold on to the landscape thanks mostly to luck and perseverance.

The next stop of the day departed a bit from the GoT theme. The Giant’s Causeway wasn’t a location in any season of the show, but it could have been – this forest of hexagonal basalt columns rising out of the sea has been an attraction for centuries. Like Skellig Michael, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, formed by volcanic activity 50-60 millions years ago, and the inspiration for legends about giants striding across the sea to Scotland. It’s a famous and well-managed tourist destination, with a visitor’s centre that was brand new when we visited, featuring a rather excellent gift shop full of quality local crafts.

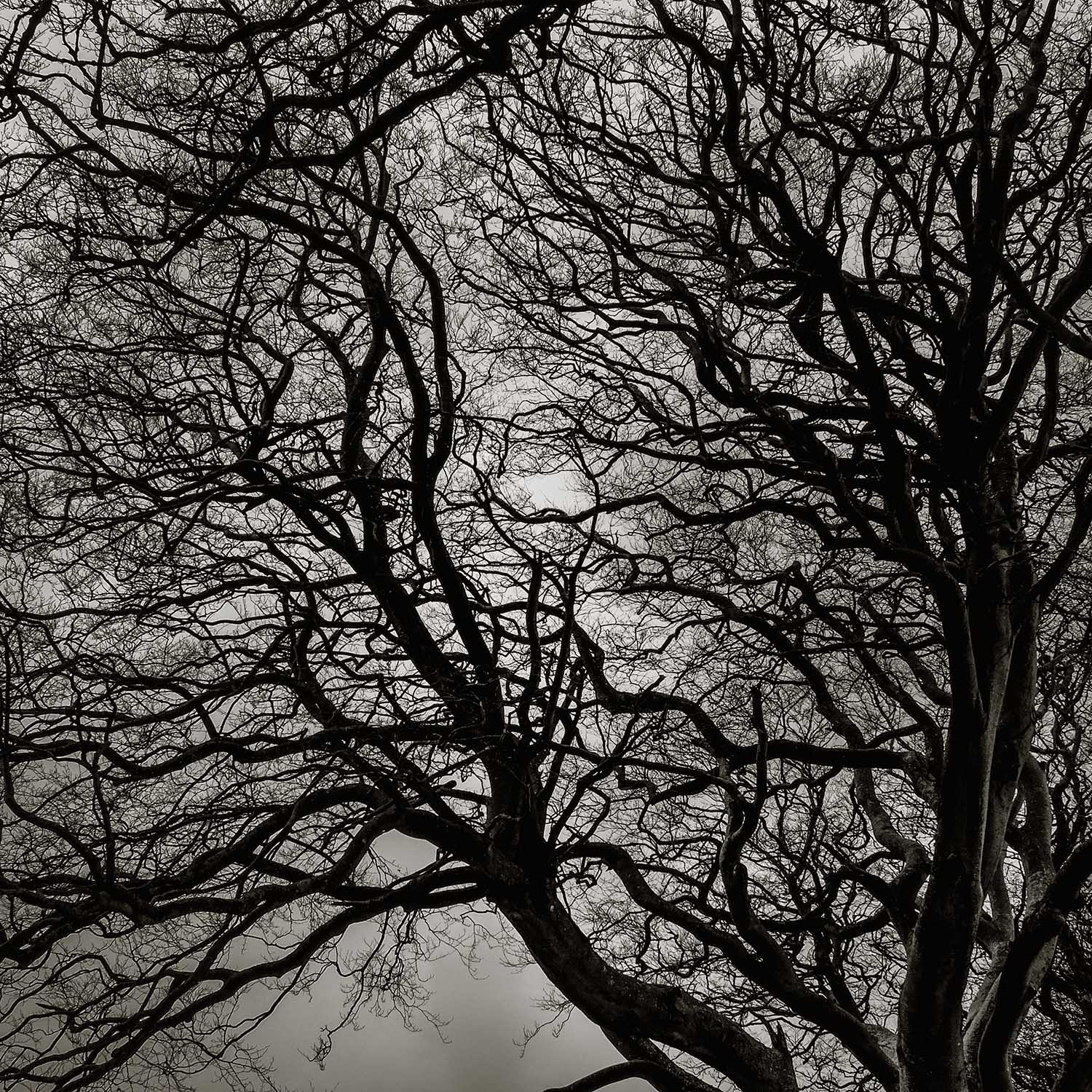

The Dark Hedges near Ballymoney are another Northern Ireland attraction whose fame long preceded Game of Thrones. This avenue of beech trees was planted over two centuries ago by the owners of nearby Gracehill House to make the coach ride to their front door more impressive. It was featured in season two, in scenes where Arya Stark is on the Kingsroad after the beheading of her father, disguised as a boy and on the run from the Lannisters. The twisting limbs of these ancient trees are like tentacles or floating hair silhouetted against the sky – a priceless spot for photos.

Our day ended at Portstewart Strand – the long, curving beach near the town of Portstewart, whose wide grasslands became the balmy coast of Dorne in season five. This was where Jaime Lannister and fan favorite character, Bronn the sellsword, try to sneak into Dorne to rescue Jaime’s niece/daughter and fight a patrol of soldiers on the dunes. Suitably, the day had become mild, the sun broke through the clouds, and we got to enjoy what is probably the finest beach I’ve ever seen this far north of the equator.

Our last day went south from Belfast into County Down – ironically taking us into the North of Westeros, to Winterfell and beyond the Wall. Our first stop was at Old Castle Ward, and the pair of 17th century defensive towers that became Winterfell, ancestral home of the Starks, in the early seasons of the show. The massive estate’s farmyard and its towers were hosting a Game of Thrones experience, with a tour of locations in or near the castle, archery, mock battles and a luncheon.

Costumed guides provided helpful explanations of the filming and the special effects that transformed the locations, as well as humorous coaching for the archery and battles. On the way from the Old Castle we stopped to admire the newer Castle Ward – an utterly picturesque mansion nestled in a landscape straight out of an old painting. It’s a truly eccentric building – the side facing the road is neoclassical Georgian, but the side looking over the lawns to Strangford Lough is Gothick.

The manor’s split personality was the result of a compromise between the builder, Bernard Ward, 1st Viscount Bangor, and his wife, Lady Anne. The building might be remarkable, but the compromise wasn’t ultimately successful, and Lady Anne left her husband shortly after the building was completed in 1770. Known for her whimsical and emotional nature, Lady Anne had a streak of madness in her family, with a brother who was famously convinced that he was a tea pot.

Our next stop was Inch Abbey, the ruins of a Cistercian Abbey founded in the 12th century and abandoned after the dissolution of the Catholic Church by Henry VIII in 1541. It became the site of Robb Stark’s camp in the Riverlands near the end of season one, the site of Robb’s coronation as “King in the North” when the North rebels after the execution of Ned Stark. Further along that morning’s route was Audley’s Castle, another defensive tower, and the scene of one of Robb’s camps in season two, where he meets Talitha, the healer who will become his wife and die with him at the Red Wedding. Just up the shore of Strangford Lough from Castle Ward, it was built in the 15th century and sold to the Ward family in 1646, and our guides kit us out with wooden swords for a mock battle beneath its walls.

Our final stop took us right back to the pilot episode of Game of Thrones, and the scenes that set up the menace hovering over most of the subsequent eight seasons. The gothic gatehouse at the entrance to Tollymore Forest Park hints at the landscape you’ll find on the other side – a place full of grottos and stone follies, woodlots and exotic woodlands, designed under the influence of Thomas Wright of Durham in the 18th century by the owner, his friend, James Hamilton, Viscount Limerick and 1st Earl of Clanbrassil.

Its oak trees would be valued for their fine quality, and would end up in the first class interiors of White Star liners like the Titanic. Hamilton’s descendants would later gift the forest to the government of Northern Ireland in the 1950s. Archaeology done in the park would discover human presence here going back beyond the Bronze Age to the Neolithic period.

A clearing among the trees is the spot where, in the first scenes of the pilot episode, rangers of the Night’s Watch cross beyond the Wall into the Haunted Forest, fatally encountering the White Walkers and their army of the undead. Nearby, a bridge over the Shimna River marks the place where Ned Stark and his sons encounter a dead direwolf and her litter of puppies, which are given to his children to raise.

You can see why the filmmakers were drawn to this magical, haunted place, and all of these other locations across Northern Ireland. They’re thick with mood and beauty and menace, depending on which way you look, a gift to anyone tasked with the job of world-building. The bonus beyond the fantasy is all the actual history contained in each of these locations – some of it stranger than anything you could imagine in a story.

Rick McGinnis was hosted by Tourism Ireland and Discover Northern Ireland, who did not approve or review this story.

Photos and story © 2016, 2017, 2021 Rick McGinnis All Rights Reserved

[…] Rick McGinnisIreland, 2016 […]

LikeLike

[…] Rick McGinnisThe Dark HedgesIreland, 2016 […]

LikeLike

[…] of trips I’d taken back when I was doing travel for the Toronto Star – to places like Ireland (north and south), Montana, Alabama, Algoma, Los Angeles, and through the Rockies on a luxury train. It was nice to […]

LikeLike